HISTORY OF CAMISSA PEOPLE – The 5 million[1] African-Creole people of South Africa – aka Coloured

The story of how over 150 tributaries creolised in coming together over 400 years to give birth to the African people who celebrate their Camissa ancestral and cultural heritage. CONTENT

CONTENT

- Introduction to the Peopling of South Africa

- Part 1: The ‖Ammaqua Founders of the Camissa Port of Table Bay

- Part 2: Camissa People of the Cape – Africans & Malagasy

- Part 3: Camissa People of the Cape – Indians, Sri Lankans & Bengalis

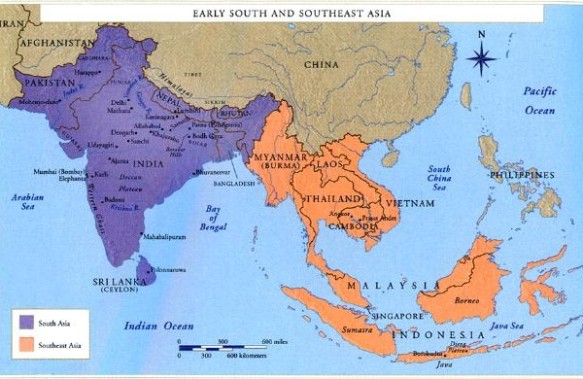

- Part 4: Camissa People of the Cape – The Southeast Asians (incl. China & Japan)

- Part 5: Camissa People of the Cape – Other Migrants of Colour

- Part 6: Camissa People of the Cape – Non-Conformist Europeans

- Part 7: Camissa – Loss of land, livestock, resources, sustainable livelihoods, cultural cohesion, loss of liberty and identities

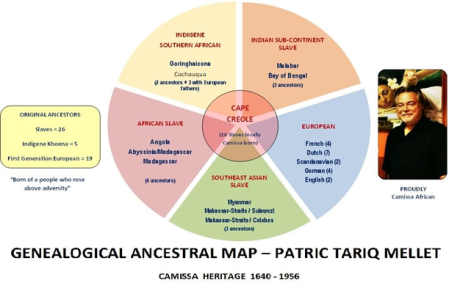

- Conclusion: Camissa People of the Cape – Genealogy & DNA Genetic testing

INTRODUCTION

The African population of South Africa (2018) is 51 757 200 at 89.7% of the total population. Of this figure the Camissa African people number 5 074 300 who are 8.8% of the total population. There are also Afro-Europeans and Europeans who number 4 520 100 who are 7.8% of the total population; and Afro-Asian and Asians who number 1 448 300 of the total population[2]. In South Africa as a hangover from the Apartheid era social scientist still use colour-race coding of white, black, coloured and Indian/Asian when projecting statistics. This does not do justice to the ancestral-cultural identities of South Africans.

All over Africa and its Island countries in every port city there are populations of African-Creole people who are a multi-ethnic mix with the major part of their ancestral heritage and culture being African. But as a result of the slave trade and maritime traffic on the Atlantic and Indian Ocean coastlines they also have in their genealogical and genetic ancestral-cultural heritage a mix of African, Indian, Arab, Southeast Asian, and Chinese and European roots. Under British colonial administration from 1911 people with this ancestry who have over 150 tributaries to their ancestral heritage were forcibly assimilated into one ‘race-silo’ labelled COLOURED and de-Africanised by colonial decree.

Many have difficulty understanding the South African race-classification separating ‘Black’ and ‘Coloured’. This terminology was a fundamental part of the Apartheid construct in ethnicising the word ‘Black’ to mean only persons of predominantly Sub-Saharan African descent and who speak languages of the Bantu linguistic family, from those of African-Creole ancestry labelled COLOURED speaking Afrikaans, English or Nama/Khoekhoegowab languages. Today many so labelled under Apartheid, in rejection of colonial and Apartheid terms and social constructs, are embracing an African consciousness and either expressing their affinity to the San and Khoi identities from which they were separated, or self-identify as Camissa Africans of African-Creole heritage. From 2018 the state has restored and recognised the African ancestral-cultural sub-identities of the San, Nama, Korana, Griqua and Cape Khoi which previously were part of those classified by Apartheid as ‘Coloured’. The larger number of those so classified have campaigned for the state to also recognise that they are Africans of Camissa or African-creole ancestral and cultural heritage, and to stop formal use the term ‘Coloured’ completely[3].

The term COLOURED is unfortunately still used by the state but it is widely challenged as it implies an acceptance of de-Africanisation in the same way as it was intended in 1911. In the run up to establishing the Union of South Africa, in 1903 a census committee[4] sat down in Pretoria and deliberated at a mini conference as to who should be classified, as what, in the new British Union of South Africa after the English victory in the Boer War. The 1904 census[5] was the last census of the Cape Colony and from the 1911 census[6] new race categories were created. The term ‘Coloured’ had been used since around 1838 by the Cape Liberal tradition but in different was to the use from the 20th century. It traversed a path where it was first used to denote all persons of colour – the ‘Coloured-Classes’, then as the ‘Native Coloureds’ for slave descendants and conquered Africans, and then for all persons of colour who spoke only English, Afrikaans, and Khoi languages and were not of predominantly Sub-Saharan African descent.

Up until the 1904 census of the Cape Colony, and from the time of Emancipation of Slavery in 1834, effective from 1838, the British used the term COLOURED in a different manner where it simply meant ‘all people of colour, as can be illustrated by the liberal Colonial Secretary in London in 1853, the Duke of Newcastle when he argued the case for continuation of the qualified franchise for the ‘Coloured Classes’.[7]

The colonial administration would report to the British Parliament on all Coloured classes of British South Africa in which were included those they called ‘Kaffers, Mfengu, Bechuanas, Sothos’, after the territories of these peoples were incorporated into the Cape Colony, as well as ‘Bushmen, Hottentots and mixed-other’. But after the Union of South Africa was formed and in the census of 1911[8] those called ‘Kaffers, Mfengu, Bechuanas and Sothos’ by the colonial administration were collectively called NATIVES and numbered 1 424 707. Those NATIVES who had the vote as qualifying ‘Coloured classes’ of the Cape were soon separated from and no longer referred to as ‘Coloured’. They were also disenfranchised under the Union Government. The notion of ‘Coloured Classes’ meaning all persons of Colour disappeared as the colonial administration used the new terminology of the NATIVE RACE and the COLOURED RACE.

In the 1911 census all other Africans were forcibly assimilated into a newly defined COLOURED group race-silo. This included those who in 1904 census[9] were noted as Bushmen (San) numbered 4 186, Hottentots (Khoi) with sub-groups Nama, Korana, Griqua, Hill Damara and Cape Hottentots and numbered 92 181, plus those called mixed-other numbering 288 151 including African-Asian slave descendants, Free Black descendants, Liberated Africans descendants, descendants of other migrants of colour and descendants of some Europeans who had assimilated into the African-Creole population whom some self-identify as Camissa Africans[10].

In 1950 the white nationalist APARTHEID regime in a definition which was as clear as mud defined COLOURED people legislatively for the first time in the POPULATION REGISTRATION ACT OF 1950[11] and the GROUP AREAS ACT OF 1950[12] and created seven sub-classifications – Cape Coloured, Malay, Griqua, Other Coloured, Indian, Chinese and Other Asian. In 1958 three of those categories were taken out of the COLOURED group and a new group known as ASIATICS was created for Indian, Chinese and Other Asians. This race classification legislation was abolished in 1990. To facilitate this Nazi-type social engineering a RACE CLASSIFICATION BOARD was established and a range of laws were passed to ensure separation (Apartheid) between the four race-silos.

The Apartheid Regime after 1978 promoted a new propaganda concept of counter-posing ‘Black Race’ and the ‘Brown Race’ to further the ends of ‘Divide and Rule’. The legacy of this indoctrination war on the one hand and the failures post 1994 to deal with de-Africanisation of ‘Coloured’ people is well illustrated by the documentary “I’m not Black…. I’m Coloured”[13]. Through the education system, Christian fundamentalist churches, and the Cape Coloured Corps in the S A Defence Force, a counter-insurgency policy called the ‘Total Strategy’[14] with a propaganda element called ‘Stratcom’ began a concerted indoctrination campaign complete with skewed history that spoke of a black colonial invasion of the brown people’s land. This aimed to influence those categorised as Coloured to see themselves as ‘Brown’ and ‘non-Black’ and in some areas the indoctrination drive attained a degree of success in whipping up a Brown-Afrikaner quasi-nationalism. It also specifically countered the Black Consciousness Movement drive for maximum black unity across the three race silos into which people of colour had been forced[15]. This approach by the liberal wing of white Afrikaner nationalism to try and extend their fortunes by abusing ‘Coloured’ people for political purposes goes way back to the 1920s in the history of the National Party but had only ever attracted limited support in the past.[16]

As the Apartheid State increasingly Nazified it created a State Security Council[17] with two counter-subversion arms – the Civil Cooperation Bureau and the Joint Management Centre that pervaded Gestapo-style every aspect of life and part of this was its WHAM project – Winning Hearts and Minds to its new ideological vision to create a united front of whites with Coloureds and Indians in a drive against the non-racial national liberation resistance. But regardless of these strategies by 1990 the Apartheid ideology had run its course making too little concessions too late, and in 1994 white colonial minority rule came to an end.[18]

This record unpacks the different components of the rich heritage of the Peopling of the Cape Colony as it relates to those who were labelled COLOURED. It offers a simple historical progression on how the African-Creole or Camissa[19] heritage traces back 3000 years to the first peopling of South Africa and also to the end of the 16th century when international shipping first frequented the Cape of Good Hope in large numbers with thousands of African, Arab, Asian and Europeans stopping off at Table Bay hosted by the indigenous people who ran the first port operations – Autshumao and the ‖Ammaqua (Watermen) at their Camissa River settlement[20].

Part 1: The ‖Ammaqua Founders of the Camissa Port of Table Bay

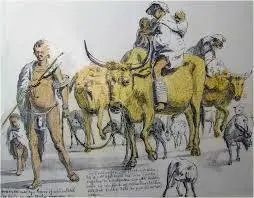

When Jan van Riebeeck arrived in Table Bay in 1652 a successful proto-port operation already existed and it was run by a Khoi (Khoe) trading-community which had broken with tribal life some 20 years earlier. They called themselves the ‖Ammaqua which the Europeans translated as the “Watermans”.[21]

When Jan van Riebeeck arrived in Table Bay in 1652 a successful proto-port operation already existed and it was run by a Khoi (Khoe) trading-community which had broken with tribal life some 20 years earlier. They called themselves the ‖Ammaqua which the Europeans translated as the “Watermans”.[21]

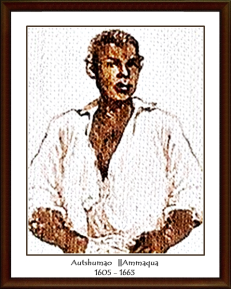

The ‖Ammaqua were among a number of other Khoi who had broken away from the main tribes, and these included independent farmers as well as outcasts from the Cochoqua, Goringhaiqua and Gorachouqua tribes who had joined the Sonqua line-fishermen who the Dutch called Strandloopers. Together all of those who left the main tribes were referred to disparagingly by other Khoi as Goringhaicona – “our kin who left us”. The founder of the ‖Ammaqua traders was a man who came to be known as Autshumao.[22]

The name ‖Au-tsâma-ao translates as “a man who swims about with fish” …… a likely reference to his sea travels to Java and his frequent boat trips back and forth to Robben Island). [23]

As their shipping to East Asia increased, the English East India Company (EEIC) decided to establish a support colony at the Cape using a small group of ten convicts from Newgate Prison but it all quickly went wrong. It started in 1613 when they kidnapped two young Khoi men and sailed for England. One of the men died en route but the other, Xhore of the Gorachouqua-Goringhaiqua people, was given an orientation to the English  ways and needs and then returned to Table Bay by the end of 1614 as an agent for English shipping interests. In 1615, when the English convict settlers arrived, the whole project floundered when Xhore drove the group from the mainland, to take refuge on Robben Island, after a conflict arose around the aggressive behaviour of the settlers towards indigenes. The survivors returned to England three years later. Xhore continued as an agent for the EEIC until around 1626 when he is said to have been killed by Dutch seamen for refusing to assist them after an altercation.[24]

ways and needs and then returned to Table Bay by the end of 1614 as an agent for English shipping interests. In 1615, when the English convict settlers arrived, the whole project floundered when Xhore drove the group from the mainland, to take refuge on Robben Island, after a conflict arose around the aggressive behaviour of the settlers towards indigenes. The survivors returned to England three years later. Xhore continued as an agent for the EEIC until around 1626 when he is said to have been killed by Dutch seamen for refusing to assist them after an altercation.[24]

In 1630 another Khoi man whom the English called Hadda or Harry came to assist them and travelled to the port of Banten (Bantam) in Java with them, where they had a prospering EEIC Factory. Here ‘Harry’ did a short internship to gain proficiency in English and some of the other European languages, and to learn about the needs of the English and what they would require in Table Bay. [25]

When Harry returned in 1632, his family and followers called him Autshumao (‖Au-tsâma-ao). Autshumao and his small group of 30 people were assisted by the English to establish a shipping-support settlement on Robben Island, where now clad in European clothes Autshumao was referred to as the Governor. [26] A further number of people would join the Robben-Island community.

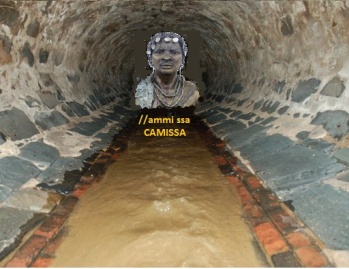

Over 5 years of this operation Autshumao’s people grew to around 60 of which the core was his extended family. By 1638 Autshumao had the English resettle them on the banks at the Camissa River mouth in Table Bay which was the most strategic position for the shipping to obtain fresh water.[27] The community which assisted the ships in loading barrels of fresh water took their name – ‖Ammaqua (Waterpeople) from the river of sweet-waters – Camissa. The indigenous name for the sea or ocean is ‖Huri and for fresh drinking water is ‖Amma. When Jan van Riebeeck arrived, as part of his tactics of subverting the ‖Ammaqua and their economy, he tried to project that they were the same people as their traditional enemies the Sonqua line-fishermen and those Khoi outcasts who had joined them. The Dutch called these people Strandloopers, but Autshumao and his people were not Strandloopers – they were the ‖Ammaqua whom the Dutch and other Europeans knew as ‘Watermans’.[28]

Over 5 years of this operation Autshumao’s people grew to around 60 of which the core was his extended family. By 1638 Autshumao had the English resettle them on the banks at the Camissa River mouth in Table Bay which was the most strategic position for the shipping to obtain fresh water.[27] The community which assisted the ships in loading barrels of fresh water took their name – ‖Ammaqua (Waterpeople) from the river of sweet-waters – Camissa. The indigenous name for the sea or ocean is ‖Huri and for fresh drinking water is ‖Amma. When Jan van Riebeeck arrived, as part of his tactics of subverting the ‖Ammaqua and their economy, he tried to project that they were the same people as their traditional enemies the Sonqua line-fishermen and those Khoi outcasts who had joined them. The Dutch called these people Strandloopers, but Autshumao and his people were not Strandloopers – they were the ‖Ammaqua whom the Dutch and other Europeans knew as ‘Watermans’.[28]

Jan van Riebeeck built his first Fort de Goede Hoop on top of the settlement of the ‖Ammaqua settlement at strategic banks the Camissa River and he over a seven year struggle usurped the port trading operations of Autshumao and his people.[29]

In the period 1600 to 1652 over 1071 outward bound ships[30] dropped anchor at Table Bay, took on water, meat, salt and timber, and recuperated their sick – all with the assistance of Khoi Traders. Likewise with homeward bound shipping. Stayovers were between three weeks and nine months. Europeans, African and Asian seamen, African-Asian slaves, soldiers en-route to fight in the East, company officials and families, all numbering over 150 000 passed through this indigene-run port. The indigenes also ran a post and communications service and a number of them had also travelled with the Europeans to far off ports and had come back. Autshumao was no ‘Beachbum’ (Strandlooper). He was a trained port-master and is noted for his love for European dress and taste for cheese, bread, wine and conversation[31]. This contrasted sharply with accounts of a dirty, ignorant, hustler strandlooper.

In the period 1600 to 1652 over 1071 outward bound ships[30] dropped anchor at Table Bay, took on water, meat, salt and timber, and recuperated their sick – all with the assistance of Khoi Traders. Likewise with homeward bound shipping. Stayovers were between three weeks and nine months. Europeans, African and Asian seamen, African-Asian slaves, soldiers en-route to fight in the East, company officials and families, all numbering over 150 000 passed through this indigene-run port. The indigenes also ran a post and communications service and a number of them had also travelled with the Europeans to far off ports and had come back. Autshumao was no ‘Beachbum’ (Strandlooper). He was a trained port-master and is noted for his love for European dress and taste for cheese, bread, wine and conversation[31]. This contrasted sharply with accounts of a dirty, ignorant, hustler strandlooper.

The different identities of ‖Ammaqua and the Strandloopers is very clear from reading primary historical texts. For the first seven years after Jan van Riebeeck’s arrival Autshumao and the ‖Ammaqua waged a relatively successful resistance to the Dutch Colony. This containment strategy was only crushed as a result of an act of betrayal in 1658 that saw Autshumao imprisoned on Robben Island. In the betrayal by a Khoi man known to the Dutch as Doman (Nommoa) the Peninsular Khoi leaders were lured into signing a treaty that signed away all of their rights to the Dutch. Doman tried to have the Dutch execute Autshumao but instead he was incarcerated on Robben Island. Everything that Autshumao fought against was challenged and turned into an agreement between the Khoi and the Dutch and the ‖Ammaqua were given over to be ruled by the Peninsula Khoena by Dutch decree.[32]

By the time the Peninsular Khoena woke up to what had happened to them as a result of the demise of Autshumao and his incarceration on Robben Island, they took to war, but it was too late. Peculiarly the war was led by the very opportunist, Doman, who had developed the disastrous peace treaty and who had delivered Autshumao to the Dutch. The first Dutch-Khoi war was lost by neither the Dutch nor the Khoi; it simply fizzled out. Autshumao’s earlier containment strategy had been more effective. The peace however was certainly lost by the Khoena, as they were expelled out of the Cape Peninsula after 1660.[33]

Autshumao had escaped from Robben Island during the war and re-joined the ‖Ammaqua who now had taken refuge in Saldanha Bay with the Cochoqua. During the war Jan van Riebeeck put a bounty on the heads of Trosoa and the other followers of Autshumao. Trosoa, the second in command to Autshumao and two others were killed in an ambush, but most of the small community escaped to the West Coast.[34] Authshumao remained the most articulate voice of resistance[35] until his death in 1663, as can be seen from the recorded statement in Jan van Riebeeck’s journal, during the negotiations after the war. With Autshumao’s death in 1663 and the permanent retreat of his ‖Ammaqua to Saldanha Bay, came an end to the story of the rise and fall over 30 years of the first port administration of what would become the City of Cape Town.

The story of Autshumao and the ‖Ammaqua people of Camissa remains the foundation reference point for the emergence of the first multi-ethnic community of African-Creole people at the Cape. From the time of Xhore starting fifteen years before Autshumao through to those cross-over years when the Dutch seized power, primary texts[36] give us clues showing that with all the interaction of those ships with their European, African and Asian crews and passengers mixing with the Khoena servicing these vessels, as with any other port in the world, sexual relations took place and children of mixed ancestry were born.

Part 2: CAMISSA PEOPLE OF THE CAPE – THE AFRICANS & MALAGASY

The majority of the people of the Cape are Africans and the term Africa first emerged among the ancient people of Kemet (Egypt) and spread in use by the Arabs, Greeks Romans. It originally was AF RUI KA – the birthplace of Humanity[37]. The term itself was  not extensively used across Africa until the advent of the 15th century Slave Trade. In South Africa the first to use the term as a means of identifying themselves were the first slaves, and the mixed descendants of slaves and Khoena (Khoi) people as per the progenitor of the Oorlams Afrikaners, Oude Ram Afrikaner and his progeny.[38] When political organisations in South Africa emerged in 1902 such as the African People’s Organisation[39] and in 1919 the African National Congress[40] (formed as the SA Native National Congress in 1912) the agreed meaning of the name AFRICAN was any person with at least one forebear who was indigenous to Africa. Originally membership of these organisations was based on that definition.

not extensively used across Africa until the advent of the 15th century Slave Trade. In South Africa the first to use the term as a means of identifying themselves were the first slaves, and the mixed descendants of slaves and Khoena (Khoi) people as per the progenitor of the Oorlams Afrikaners, Oude Ram Afrikaner and his progeny.[38] When political organisations in South Africa emerged in 1902 such as the African People’s Organisation[39] and in 1919 the African National Congress[40] (formed as the SA Native National Congress in 1912) the agreed meaning of the name AFRICAN was any person with at least one forebear who was indigenous to Africa. Originally membership of these organisations was based on that definition.

The AFRICAN roots of the People of the Cape, has six overarching tributaries:

Indigenous people of the Cape: In the South  this was the San and Khoi[41]; up along the Kai !Gariep River district it included San, Khoi, Nqgosini (Sotho-Khoi) and Gyzikoa (Tswana-Khoi)[42]; and then in the East it was the San, Khoi, Gqunukhwebe (Xhosa-Khoi) and Xhosa[43]. There had been San populations across Southern Africa and in the South these were the ǀXam and the!Kun. Later migrant herders and farmers Khoi, Kalanga, Tswana, Sotho, Xhosa and Thembu moved into these territories and each impacted on the other’s identity giving birth to multi-ethnic communities of indigenous Africans[44].

this was the San and Khoi[41]; up along the Kai !Gariep River district it included San, Khoi, Nqgosini (Sotho-Khoi) and Gyzikoa (Tswana-Khoi)[42]; and then in the East it was the San, Khoi, Gqunukhwebe (Xhosa-Khoi) and Xhosa[43]. There had been San populations across Southern Africa and in the South these were the ǀXam and the!Kun. Later migrant herders and farmers Khoi, Kalanga, Tswana, Sotho, Xhosa and Thembu moved into these territories and each impacted on the other’s identity giving birth to multi-ethnic communities of indigenous Africans[44].

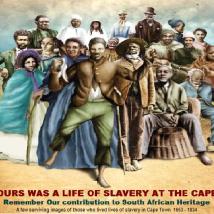

Early African Slaves: The first largest numbers of slaves were from Guinea, Angola and Cabo Verde[45]. These were followed by East Africans from Madagascar, Mozambique, Kenya (Mombassa), Ethiopia/Somalia.[46] Malagasy slaves were largely taken from the Northwestern Coast down to St Augustine Bay at the Southwest – all with strong Sub-Saharan African roots, but a number also will have come from the Northeastern Coast and Eastern coast with Arab and Somali roots, and Southeast Asian roots. From the shipping records and journals the areas from which slaves were taken are clearly stated and the slaves are referred to as Negroes.[47]

Madagascar and African Island localities of Cape Slaves[48]:

Toliary Province: Morombe, Toliary, Bezaha, Morondava, Cape San Marie, Tolerano, Maha valona, St Augustine Bay, Amboasary – Mahajanga Province: Cape St Andre, Mahajanga, Mazalagem Nova, Bombetoka Bay, Maningaar, Marovoay, Mangariek, Boina Bay, Ambanja, Analalava, Anjanjavi, Vilamatsa – Antsirana Province: Ambanja – Toamasina Province: Bay of Antogil, Moroantsetra, Seranambe, Antanambe, Morondava, Isle St Marie.

valona, St Augustine Bay, Amboasary – Mahajanga Province: Cape St Andre, Mahajanga, Mazalagem Nova, Bombetoka Bay, Maningaar, Marovoay, Mangariek, Boina Bay, Ambanja, Analalava, Anjanjavi, Vilamatsa – Antsirana Province: Ambanja – Toamasina Province: Bay of Antogil, Moroantsetra, Seranambe, Antanambe, Morondava, Isle St Marie.

Cabo Verde, St Jago, Zanzibar, Mauritius, Camores (Anjoan)

Mazbieker Slaves and Indentured labourers: From around 1770 less and less slaves were coming to the Cape from Asia with the vast majority coming from Mozambique Island. These slaves were called Mazbiekers and were captured in Mozambique, Tanzania, Malawi,  Zambia, Zimbabwe, Swaziland and northern parts of South Africa including Limpopo, Mpumalanga and KZN.[49]

Zambia, Zimbabwe, Swaziland and northern parts of South Africa including Limpopo, Mpumalanga and KZN.[49]

As a result of the emancipation from slavery in 1834, 7000 white farmers and their slaves migrated northwards away from the British colony. This together with the drift away from farms by freed slaves created a labour and economic crisis. After Emancipation from slavery, the slavery system thus quickly morphed into the Indentured Labour and Apprenticed Labour systems and Masbiekers continued to be brought into the Cape on this new basis.

Ordinance 49 of 1828 already allowed for Native Coloureds (Africans) from beyond the Colony’s borders to get passes to work in the Cape.[50] ‘Beyond the borders’ meant from British territories and from Boer territories in Southern Africa. Indentured labour was supposed to be a temporary labour solution but many did not return home and instead assimilated with the descendants of the earlier Mazbieker slaves. After 1911 like the Mazbieker slave descendants they assimilated into the newly created “Coloured” identity.

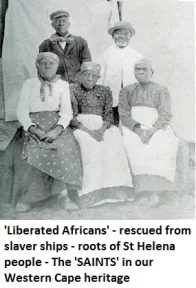

Liberated Africans[51]: From 1840 the Royal Navy had set up squadrons operating out of St Helena, Senegal, Simonstown, Zanzibar and Aden to stop the slave-trading ships on the high seas and to seize the slave cargoes referred to as “Prize Slaves” who were formally known as “Liberated Africans”. Many of these “Liberated Africans” were brought to the Cape up to around 1860, branded and not set free. Instead they became apprenticed to farmers and public works initially for a 14 year period, which then changed to five years. They too assimilated in the post 1911 ‘Coloured’ identity. The last of the ‘Liberated Africans’ to arrive at the Cape were the ship load Oromo children in 1890[52]. They had been captured by the Royal Navy interceptors based in Aden.

Liberated Africans[51]: From 1840 the Royal Navy had set up squadrons operating out of St Helena, Senegal, Simonstown, Zanzibar and Aden to stop the slave-trading ships on the high seas and to seize the slave cargoes referred to as “Prize Slaves” who were formally known as “Liberated Africans”. Many of these “Liberated Africans” were brought to the Cape up to around 1860, branded and not set free. Instead they became apprenticed to farmers and public works initially for a 14 year period, which then changed to five years. They too assimilated in the post 1911 ‘Coloured’ identity. The last of the ‘Liberated Africans’ to arrive at the Cape were the ship load Oromo children in 1890[52]. They had been captured by the Royal Navy interceptors based in Aden.

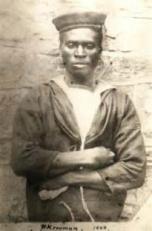

African RN Seamen: From 1840 the Royal  Navy had set up squadrons operating out of Simonstown to stop the slave-trading ships on the high seas and to seize the slave cargoes. All of the Royal Navy sailors from 1840 through to around 1938 were people of colour – from West Africans known as the Kroo; from Zanzibaris known as Seedies; and from India known as Lascars.[53] Many stayed on in Cape Town and integrated into the African Creole or Camissa Embrace.

Navy had set up squadrons operating out of Simonstown to stop the slave-trading ships on the high seas and to seize the slave cargoes. All of the Royal Navy sailors from 1840 through to around 1938 were people of colour – from West Africans known as the Kroo; from Zanzibaris known as Seedies; and from India known as Lascars.[53] Many stayed on in Cape Town and integrated into the African Creole or Camissa Embrace.

Hill Damara (Khoi): From 1879 – 1882 there were 20 shipments of (Berg) Damara to Cape Town from German West Africa (Namibia) as Indentured Labourers. Many assimilated into the ‘Mixed-Other’ population later called ‘Coloured’.[54]

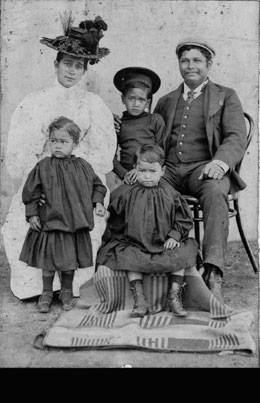

All of these different African identities interacted with each other and also interacted with Asian and Southeast Asian identities and non-conformist European identities and within two generations of various forms of unions including formal marriages creolisation took place. Creolisation simple means a new creation was born of African-Creole people who resulted from what we call – the Camissa Embrace.[55] Family genealogies and dna-testing have shown that Southern Africa dna associated with San and Khoi ancestral roots average at around 36% among those classified ‘Coloured’ and Sub-Saharan dna associated with Sub-Saharan Africans averaging around 34%. Thus the dna measure of those classified “Coloured” shows that the ancestral roots are around 70% African, with 30% India, Southeast Asian, Chinese, Eurasian and European. Test results show that the People of the Cape have the most diverse dna results in the world.[56]

Part 3. CAMISSA PEOPLE OF THE CAPE – SLAVERY: THE INDIANS, SRI-LANKANS & BENGALIS

Over the period 1652 – 1860 around 78 539 first generation slaves were brought to the Cape of Good Hope.[57] These were brought either as slaves or as ‘liberated Africans’ also known as ‘Prize Slaves’. Successive generations of children and grandchildren were also locally born into slavery. Of this number, 60.7% were from  Africa/Madagascar, 22.06% from India/Sri Lanka/Bengal and 17.24% from Southeast Asia.[58]

Africa/Madagascar, 22.06% from India/Sri Lanka/Bengal and 17.24% from Southeast Asia.[58]

Those enslaved in India, Sri Lanka and Bengal largely came from coastal districts along the west Malabar Coast and the east Coromandel Coast to West Bengal State; as well as from Shepur, Dhaka, Rajshahi in Bangladesh; and also from the ports of Galle, Colombo, and Jafnapatam (Jaffna) in Sri Lanka. The specific place names, which are recorded as toponyms from slave records[59], then translated into the modern place names, that can be directly linked to India and Bengal include:

- GUJARAT STATE: Surat, Cambay (Khambhat), Broach (Bharuch or Bhrugukachchha)

- MAHARASHTRA STATE: Mumbai, Vengurla,

- GOA STATE: Panaji, Sankhali

- KARNATAKA STATE: Mangalore, Rotti (Rotti-kallu)

- KERALA STATE: Cochin (Kochi), Callicut (Kozhikode), Vaypin, Ajengo,

- TAMIL NADU STATE: Thengapattanam, Negapatam (Nagapattinam), Pondicherry (Puducherry), Madras (Chennai), Tranquebar (Tharangambadi), Tuticorin (Thoothukudi), Palicatte or Pulicat (Pazhaverkadu) which was the Dutch slavery centre in India Castle Geldria, Porto Novo (Parangipettai),

- ANDHRA PRADESH STATE: Masulpatnam or Bandar (Machilipatnam), Vishakhapatam (Vizag),

- ODISHA STATE: Fulta (Phulta), Balasore (Baleshwar), Baliapal (Pipeli),

- WEST BENGAL STATE: Calcutta (Kolkata), Hoogly (Chinsura), Cossimbazar (Kasim Bazar), Mirzapur, Murshidabad,

- BIHAR STATE: Pattna or Patna (Pataliputra), Chhapra,

These enslaved people became slaves as a result of four main means[60]:

- They were war captives from European and Arab colonial conflicts with indigenous communities; inter-ethnic wars in the region; and inter-colonial wars in which local communities would be caught up.

- They were refugees from natural disasters such as famine, drought, floods, quakes and tsunamis which often devastated large areas and suddenly rendered populations vulnerable.

- They were people kidnapped by pirates for quick economic gains, sometimes even per order for special exploitation such as with concubines.

- They were people whose families were in debt to overlords and money-lenders who were forced to give up their family members into debt-bondage.

Notably all of these reasons still apply in the region today where slavery is now called HUMAN TRAFFICKING[61].

The enslaved are from 40 centres across 3 countries and 10 states within India which is an array of different cultures languages and dialects, faiths, histories and traditions. These were all Dutch trading bases at Galle, Colombo, Cochin and Palicatte were major slaving stations in this arena. This large multi-ethnic Indian or Dravidian forced migration to the Cape via the Mauritius halfway station[62] took place over a 120 year period which ended 100 years before the large wave of Indian Indentured labourers and passenger Indians were brought to KZN by the British. It should be noted that up to 50% of the enslaved died during transportation across the sea voyages.[63]

Passenger economic-migrant Indians also came to the Cape from 1770 onwards as can be seen in the Free Black marriages as demonstrated the genealogical records.[64] The vast majority of these Indians, Sri Lankans and Bengalis (slave and Free Black) assimilated at the Cape with the African slaves and Southeast Asian slaves and other Free Blacks. Children were also born to mixed local indigenes who had relationships with the slaves and also from European unions and marriages with slaves. Within generations creolisation had occurred and there are little easily visible signs of a stand-alone Indian, Sri Lanka and Bengali ethnicity today. These tributaries from India, Sri Lanka and Bengal are part of a broader African-Creole people who make up the Camissa Embrace.

Passenger economic-migrant Indians also came to the Cape from 1770 onwards as can be seen in the Free Black marriages as demonstrated the genealogical records.[64] The vast majority of these Indians, Sri Lankans and Bengalis (slave and Free Black) assimilated at the Cape with the African slaves and Southeast Asian slaves and other Free Blacks. Children were also born to mixed local indigenes who had relationships with the slaves and also from European unions and marriages with slaves. Within generations creolisation had occurred and there are little easily visible signs of a stand-alone Indian, Sri Lanka and Bengali ethnicity today. These tributaries from India, Sri Lanka and Bengal are part of a broader African-Creole people who make up the Camissa Embrace.

Tell-tale whispers of these ancient cultures can be found in the African-Creole cuisine, faith practices, song, dance and expressions in the broader Camissa African communities labelled “Coloured”.

In the 21st century new economic migrants from these same areas have made their way to South Africa, and the Cape. The Camissa Embrace continues to add further dimensions in the coming together – or PEOPLING OF THE CAPE.

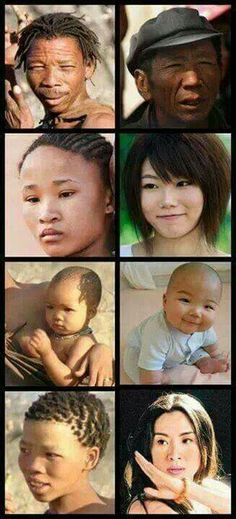

Part 4. THE PEOPLING OF THE CAPE – SLAVERY: THE SOUTHEAST ASIANS (including China and Japan)

Over the period 1652 – 1860 around 78 539 first generation slaves were brought to the Cape of Good Hope.[65] These were brought either as slaves or as ‘liberated Africans’ also known as ‘Prize Slaves’. Successive generations of children and grandchildren were also locally born into slavery. Of this number 60.7% were from Africa/Madagascar, 22.06% from India/Sri Lanka/Bengal and 17.24% from Southeast Asia.[66]

The places from which Southeast Asian, Chinese and Japanese slaves were taken and brought to the Cape, as are demonstrated in the toponyms of first generation slaves and in ships records, were[67]:

Myanmar (Arakan or Rakhine); Laos; Thailand (Siam); Vietnam (Tonkin or Hanoi); Cambodia; Singapore; Malaysia; Borneo; New Guinea; Philippines (Manila); Indonesia – (SUMATRA: Nias; Mannacabo; Padang; Djambi; Soekadana;) (JAVA – Jakarta (Batavia); Cheribon; Tegal; Semarang; Rembang; Soerabaya;) BALIi; SOEMBAWA – Bima; SOEMBA– Mangerai; Endeh; SALOOR; ALOR; TIMOR (East Timor independent); ROMA; BANDA; AMBON; MADOERE; FLORES; SATEIER; BOETEN; SULAWEZI / CELEBES – Makassar; Sanpeng; Menado; and the Boegies people) MOLACCAS; TERNATE;

Myanmar (Arakan or Rakhine); Laos; Thailand (Siam); Vietnam (Tonkin or Hanoi); Cambodia; Singapore; Malaysia; Borneo; New Guinea; Philippines (Manila); Indonesia – (SUMATRA: Nias; Mannacabo; Padang; Djambi; Soekadana;) (JAVA – Jakarta (Batavia); Cheribon; Tegal; Semarang; Rembang; Soerabaya;) BALIi; SOEMBAWA – Bima; SOEMBA– Mangerai; Endeh; SALOOR; ALOR; TIMOR (East Timor independent); ROMA; BANDA; AMBON; MADOERE; FLORES; SATEIER; BOETEN; SULAWEZI / CELEBES – Makassar; Sanpeng; Menado; and the Boegies people) MOLACCAS; TERNATE;

CHINA: Formosa (Taiwan); Kwangtung (Canton China – Peoples Rep China); Macau; Hong Kong (Peoples Rep China);

JAPAN (Deshima)

The largest numbers of enslaved from this region came from the Indonesian archipelago which at that time was an area of high contestation between the Portuguese, Dutch, English, French, Danish, Spanish and other lesser European powers and also between these and the Arab established Sultanates. There were also conflicts between the Europeans and the Indigene kingdoms, between indigene and indigene, and Arab conquests of indigenes. All of this conflict produced war captives who were sold into slavery. The Dutch Massacre of 10 000 Peranakan Chinese in Batavia in 1740 also resulted in the forced transfer of Chinese to the Cape[68].

These enslaved people became slaves as result of three other means[69]:

- They were refugees from natural disasters such as famine, drought, floods, quakes and tsunamis which often devastated large areas and suddenly rendered populations vulnerable.

- They were people kidnapped by pirates for quick economic gains, sometimes even per order for special exploitation such as with concubines.

- They were people whose families were in debt to overlords and money-lenders who were forced to give up their family members into debt-bondage.

Notably all of these reasons still apply in the region today where slavery is now called HUMAN TRAFFICKING[70].

The enslaved are from across 15 countries, and in the case of Indonesia from 18 Islands and 18 sub-areas which have an array of different cultures, languages and dialects, faiths, histories and traditions. A country like the Kingdom of Siam also established diplomatic relations with Simon van der Stel at the Cape in 1686 after the rescue of the Siamese ambassador who had been shipwrecked in Agulhas.

This large multi-ethnic forced migration to the Cape via the Mauritius halfway station continued until it tapered off in the 1780s and it should be noted that up to 50% of the enslaved died during transportation across the sea voyages.[71] The vast majority of the  Southeast Asians, Chinese and few Japanese assimilated at the Cape with the African slaves and Indian, Sri Lankan and Bengali slaves. Children were also born to mixed local indigenes who had relationships with the slaves and also from European unions and marriages with slaves. Within three generations creolisation had occurred and there is no stand-alone survival of these ethnicities today. These tributaries from Southeast Asia, China and Japan are part of a broader African-Creole people who make up the Camissa Embrace.

Southeast Asians, Chinese and few Japanese assimilated at the Cape with the African slaves and Indian, Sri Lankan and Bengali slaves. Children were also born to mixed local indigenes who had relationships with the slaves and also from European unions and marriages with slaves. Within three generations creolisation had occurred and there is no stand-alone survival of these ethnicities today. These tributaries from Southeast Asia, China and Japan are part of a broader African-Creole people who make up the Camissa Embrace.

Elements of these ancient cultures through an African creolisation process can be found in cuisine, faith practices, song, dance and expressions in the broader Camissa African communities labelled “Coloured”. After a number of Indonesian religious and political leaders were forcibly exiled to the Cape they did a lot of missionary outreach work among the slaves, most of whom were not Muslim when they came to the Cape.[72] Through this influence a mix of Arab and Indonesian cultures found a special niche in Cape culture and survive to this day both in the constructed identity of those who chose to call themselves Cape Malays and the larger numbers who share the same multi-ethnic roots.

Elements of these ancient cultures through an African creolisation process can be found in cuisine, faith practices, song, dance and expressions in the broader Camissa African communities labelled “Coloured”. After a number of Indonesian religious and political leaders were forcibly exiled to the Cape they did a lot of missionary outreach work among the slaves, most of whom were not Muslim when they came to the Cape.[72] Through this influence a mix of Arab and Indonesian cultures found a special niche in Cape culture and survive to this day both in the constructed identity of those who chose to call themselves Cape Malays and the larger numbers who share the same multi-ethnic roots.

Under the British social engineering in the mid-19th century separated out Christian and Muslims from the same mixed African-Creole people with roots across Southeast Asia, Africa-Madagascar, and India, Sri Lanka and Bengal, and called the Cape Muslims – Malays. The use of the term Malay was not derived from Malaysia but rather from the Meleyu language used by slave traders and the pan-Meleyu family of ethnicities. This was taken to a higher level in the mid-20th century by the Apartheid National Party ideologue ID du Plessis[73] who promoted a segregated Cape Malay nationalism. Effectively this resulted into some adopting the Cape Malay constructed identity.[74] A small sector of our  society freely choose to project this as their identity but the larger Cape Muslim community do not, and neither do the larger numbers of Southeast Asian slave-descendants who are Christian, Buddhist, Hindu, Syncretic faith or of no faith. But all enjoy good relations. The world of 16th and 17th century Southeast Asia was very different then in relation to now. Cape Malays also have strong African, Indian, Sri Lankan, Bengali and Chinese ancestry and cultural roots.

society freely choose to project this as their identity but the larger Cape Muslim community do not, and neither do the larger numbers of Southeast Asian slave-descendants who are Christian, Buddhist, Hindu, Syncretic faith or of no faith. But all enjoy good relations. The world of 16th and 17th century Southeast Asia was very different then in relation to now. Cape Malays also have strong African, Indian, Sri Lankan, Bengali and Chinese ancestry and cultural roots.

In the 21st century new economic migrants from these same areas have made their way to South Africa and the Cape, and Camissa in embracing them continues to add further dimensions in the coming together – or PEOPLING OF THE CAPE. A popular Cape expression is “Make the Circle Bigger!”

Part 5. CAMISSA PEOPLE OF THE CAPE – OTHER MIGRANTS OF COLOUR

From 1652 through to the formation of  the Union of South Africa in 1910 when the British Cape Colony ended as an entity there were various forced and voluntary migrations of people of colour to the colony. Indeed until the mid-19th century there were marginally more migrants of colour than Europeans, and a large proportion were Africans.[75]

the Union of South Africa in 1910 when the British Cape Colony ended as an entity there were various forced and voluntary migrations of people of colour to the colony. Indeed until the mid-19th century there were marginally more migrants of colour than Europeans, and a large proportion were Africans.[75]

The first interactions between local indigene Africans and people of colour from abroad – Africans and Asians, would have taken place during the increased period of shipping in the half-century before the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck. By calculating the full complement of people on board vessels (1071 outward bound and 800 homeward bound)[76] – officials, soldiers, passengers, slaves and sailors on board show that over 150 000 visitors had come to Table Bay between 1600 – 1652 which from 1615 was a compulsory stop-over. The seamen as was the custom of that time were Africans, Asians, Arabs and Europeans – and many, especially given the long stay-overs between 3 weeks and 9 months, would have had sexual relations with indigenes like in any other port in the world, from which children were born. References in primary research documentations show comments about the features of some among local communities that attest to such births.[77]

But from 1652, besides the arrival of slaves, there were people of colour – Free Black soldiers (Merdijkers from Ambon), sailors, officials, travellers, exiles, convicts, refugees, stow-aways, indentured labourers, merchants and adventurers who settled and integrated with others at the Cape.[78] There were also whole populations of black-Portuguese, mestizo-Dutch and other Creole or Eurasians from Dutch colonies across the Indian Ocean territories who came to the Cape. An example of such was Governor Simon van der Stel whose father was Dutch and his mother was a daughter of an Indian slave. One of the charges levelled at Governor Willem Adrian van der Stel was that the Europeans considered him to have the blood and temperament of the ‘oriental potentate’ and ‘the black brood among us’.[79]

But from 1652, besides the arrival of slaves, there were people of colour – Free Black soldiers (Merdijkers from Ambon), sailors, officials, travellers, exiles, convicts, refugees, stow-aways, indentured labourers, merchants and adventurers who settled and integrated with others at the Cape.[78] There were also whole populations of black-Portuguese, mestizo-Dutch and other Creole or Eurasians from Dutch colonies across the Indian Ocean territories who came to the Cape. An example of such was Governor Simon van der Stel whose father was Dutch and his mother was a daughter of an Indian slave. One of the charges levelled at Governor Willem Adrian van der Stel was that the Europeans considered him to have the blood and temperament of the ‘oriental potentate’ and ‘the black brood among us’.[79]

These are the array of waves of migrants of colour who are also the ancestors of those of African-creole or Camissa heritage, labelled ‘Coloured’ under Apartheid classification[80]:

THE WALI EXILES[81]: Sumatra ; Java; Sulawezi (Makassar); Jakarta (Batavia); CHINESE EXILES[82]: Peranakan (Creole-Chinese from Batavia); PHILIPPINES REFUGEES[83]: Manila; CONVICTS[84]: From across the Dutch footprint in India and Southeast Asia and China; MIGRANT SAINTS[85]: St Helenians (3 waves), and Chinese indentured labourers who came to the Cape from St Helena after completion of their indentureship rather than returned to China; ROYAL NAVY ANTI-SLAVER SEAMEN[86]: West African Kroo; Indian Lascars; Zanzibari Seedies; CHINESE INDENTURED LABOURERS[87]: Three waves from Guangdung; PUBLIC WORKS INDENTURED LABOUR[88]: Zanzibari Seedies;

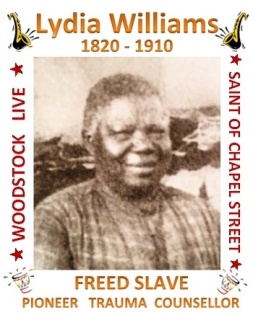

BRITISH PASSENGER INDIANS[89]: Economic migrants from across India in different waves from the late 18th century to the early 20th century – as different from the Indentured labourers that went to Natal post 1860; NATIVE COLOURED INDENTURED LABOUR[90]: Labourers for farms from British Protectorates and Southern African Territories beyond the borders of the Cape Colony. MOZAMBIQUE INDENTURES[91]: Mozambique labourers for farms; AFRICAN-AMERICANS, CARIBBEAN, AFRICAN-DIASPORA MIGRANTS[92]: Merchants; Miners; Adventurers; Sailors; Professionals (Journalists, Advocate, Entertainers, Ministers of faith); ARAB, PERSIAN & TURKISH SCHOLARS & MIGRANTS[93]: Islamic scholars of note who came to the Cape to enhance the understanding of the faith as well as merchants and professionals; AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINES[94]: Abandoned trackers of the Royal Australian Armed Forces during the Anglo-Boer War; ASIAN SEAMEN[95]: Chinese, Japanese & Indonesian Seaman; OROMO[96]: The Oromo children were brought from the RN base at Aden in 1890 after rescued from a slaver dhouw, and sent to school at Lovedale Mission; MIGRANTS OF COLOUR CONTINUED THROUGH THE 20th CENTURY and into the 21st CENTURY with the statistician-general now recording new migrants as a category in the census[97].

BRITISH PASSENGER INDIANS[89]: Economic migrants from across India in different waves from the late 18th century to the early 20th century – as different from the Indentured labourers that went to Natal post 1860; NATIVE COLOURED INDENTURED LABOUR[90]: Labourers for farms from British Protectorates and Southern African Territories beyond the borders of the Cape Colony. MOZAMBIQUE INDENTURES[91]: Mozambique labourers for farms; AFRICAN-AMERICANS, CARIBBEAN, AFRICAN-DIASPORA MIGRANTS[92]: Merchants; Miners; Adventurers; Sailors; Professionals (Journalists, Advocate, Entertainers, Ministers of faith); ARAB, PERSIAN & TURKISH SCHOLARS & MIGRANTS[93]: Islamic scholars of note who came to the Cape to enhance the understanding of the faith as well as merchants and professionals; AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINES[94]: Abandoned trackers of the Royal Australian Armed Forces during the Anglo-Boer War; ASIAN SEAMEN[95]: Chinese, Japanese & Indonesian Seaman; OROMO[96]: The Oromo children were brought from the RN base at Aden in 1890 after rescued from a slaver dhouw, and sent to school at Lovedale Mission; MIGRANTS OF COLOUR CONTINUED THROUGH THE 20th CENTURY and into the 21st CENTURY with the statistician-general now recording new migrants as a category in the census[97].

As European migration grew numerically stronger during the late 19th Century and 20th Century there was a few non-conformists among them that assimilated into African-Creole or Camissa communities. For example from among the Jewish migrant refugees from the pogroms and economic hardships in Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania and Russia some settled in District Six and married or had children with local people.

Here we can see 20 more tributaries into the African-Creole or Camissa Embrace at the Cape. Each of these has multiple sub-tributaries.

THE DROSTER AND OORLAMS – 18th & 19th Century KHOI REVIVALISM: Another phenomenon was that escaped slaves known as Drosters as well as Oorlam groups, and Cape Khoi refugees, who sought refuge among the Nama, Kai !Gariep Khoi and San and among the Xhosa in the Eastern Cape. Up at the Kai !Gariep territory this phenomenon was an extension of  the African-Creole or Camissa Embrace and took place over a 100 year period from 1750 – 1850.[98] Likewise a similar process of Maroons was taking place along the wild-coast of the Eastern Cape from 1600 right through to the 19th century and included marooned survivors of shipwrecks on the wild coast.[99] In Kwazulu-Natal and in Gauteng and the northern territories there were similar lesser impacts. In the Eastern Cape marooned African and Asian seamen or slaves and passengers stranded through shipwrecks, together with some European shipwreck survivors assimilated into Xhosa and Khoi communities.[100]

the African-Creole or Camissa Embrace and took place over a 100 year period from 1750 – 1850.[98] Likewise a similar process of Maroons was taking place along the wild-coast of the Eastern Cape from 1600 right through to the 19th century and included marooned survivors of shipwrecks on the wild coast.[99] In Kwazulu-Natal and in Gauteng and the northern territories there were similar lesser impacts. In the Eastern Cape marooned African and Asian seamen or slaves and passengers stranded through shipwrecks, together with some European shipwreck survivors assimilated into Xhosa and Khoi communities.[100]

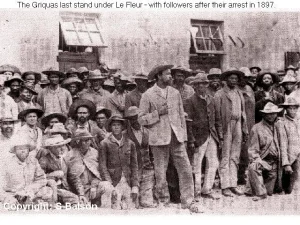

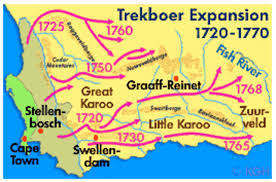

At the Kai !Gariep refugee Khoi from the Cape wars of resistance including refugees from the enforced conscription and quasi-slavery imposed on Khoi on European farms, formed what were called Oorlam groups – the Bergenaar Basters (which became the Griquas), the Korana, the Oorlam Afrikaners, the Springboks and the Witboois.[101] Joining them were European rebels who fled the colony as well as Tswana, Sotho and Xhosa drifters. All of these revived Khoi groups are multi-ethnic formations with a strong Khoi foundation.[102] On the northwestern territories this regrouping of Khoi peoples with some admixture of others formed the new polities of 18th and 19th century Khoi Revivalists[103]. They organised themselves as the first manifestation of modern proto-national formations and left written record of their political views. Some would later in the 20th century migrate back to the Western Cape, most notably the Griqualand East followers of AS le Fleur, known as de Kneg van God.[104]

Thus between the Camissa River at Table Bay to the Kai !Gariep River making up the Northern boundary of the Cape Colony from the 1750s onwards there was an internal migration drift as a result of the destabilisation of mass European migration, land and livestock seizures and forced displacement of indigenous peoples. The discovery of diamonds in Kimberly was also a major catalyst for both European migration and migrants of colour in what was called the ‘Diamond Rush’.[105]

NATIVE COLOURED PEOPLE: During the Cape Liberal period the term ‘Coloured’ was used fluidly and differently to how it was used in the 20th Century. It meant ‘non-white’ or all persons of colour. Sometimes the reference was to Native Coloured People as in the South African Commercial Advertiser editorial by John Fairburn[106] or Coloured Classes, or Employed Coloureds, but gradually as the 19th century drew to a close it implied pacification or sharing European ‘civilisation’ norms as distinct from ‘uncivilised’ natives. It also increasingly became a term for people of colour who only spoke Afrikaans or English. While still under the Cape Colony all of migrants of colour, regardless of African or Asian, post-emancipation from slavery, were counted along with slave descendants as being the “Mixed-Other” component of the COLOURED CLASSES of BRITISH SOUTH AFRICA[107]. The other components who were called the COLOURED CLASSES for purposes of reports to the British Parliament were those labelled as ‘Kaffers, Fingos, Beachuanas, Koranas, Griquas, Hill Damara, Nama, Cape Hottentots and Bushmen’. In 1911 the census of the Union of South Africa separated these COLOURED CLASSES OF BRITISH SOUTH AFRICA into NATIVES and COLOURED.

Those in the previous Boer Republics, together with the Zulus, were put together with those previously labelled ‘Kaffers, Fingos and Bechuanas’ and then collectively called NATIVES. All others – ‘Mixed-Other, Mazbiekers, Liberated Africans, Cape Hottentots, Griqua, Nama, Korana, Hill Damara, and Bushmen’ were assimilated as one group labelled ‘Coloured’ in a deliberate act of de-Africanisation – a Crime Against Humanity[108]. At the last separately counted census in 1904 there were 4186 San (Bushmen), 92 181 Khoi (Cape Hottentots, Griqua, Nama, Korana, Hill Damara) and over 288 151 Mixed-Other including African-Asian Slave descendants, Mazbiekers, Liberated Africans and descendants of all other migrants of colour and the few Europeans who had assimilated with them.

When one looks at the African diversity and the numerics it clearly shows why in genetic studies the Khoi, San and Sub-Saharan African component of ‘Coloured’ or Camissa identity is around 70% and why the San and Khoi component is roughly equal to the Sub-Saharan African component. When one looks at the overall picture alongside the social history it is virtually impossible to separate out the Indian, Southeast Asia, Chinese, Eurasian and European tributaries from the African, hence the reference to African-Creolisation. Colonialism and Apartheid operated in a deeply racist framework that has left South African society highly ethnic-conscious where identity is boiled down by many as needing to be a single ethnic or race affiliation. People classified as Coloured do not and cannot fit into the racist-ethnicist framework, yet many still try to meet such a specification. Some exercise their right to self-determination by attempting to revive old cultural ethnic formations such as the Khoi of the 17th century and the pan-Malay identity but most are not so orientated and are quite comfortable in recognising their African-Creole or Camissa multi-ethnic and multi-cultural roots as the heritage which they celebrate. These two divergent trends along with those Khoi and San and other African identities that survived the many years of forced assimilation are all genuine post-Apartheid expressions of African heritage.

The use of the term Camissa, the name of the river and the name of the first indigene traders, and the indigenous name for all fresh water rivers from the Zambezi down to the Table Bay Camissa, it is a recognition that all Southern African societies came about through multi-ethnic mingling around fresh water rivers. The term also represents a clean break away from ‘race’ and ‘colour’ terminology as well as from narrow ‘ethnicism’.

Part 6. CAMISSA PEOPLE OF THE CAPE – NON-CONFORMIST EUROPEANS

European migration to the Cape started in 1652 even although there had been groups of Europeans who lived for long periods at the Cape before this date.[109] While there were European visitors to the Cape between 1488 t0 1600, mass European visitation numbering over 150 000 can first be recorded between 1600 – 1652 during which 1071 ships on outward bound journeys alone stopped off at Table Bay and stayed for durations of 3 weeks to nine months.[110] This first formal attempt at colonisation occurred in 1615 when the English East India Company settled ten Newgate Convicts at Table Bay but this was a failure[111]. In 1652 the United Dutch East India Company established a refreshment station at Table Bay and in 1657 this was expanded to create the beginning of the Cape Colony. From the earliest of maritime journeys along the wild eastern coast of South Africa ships were wrecked and marooned survivors – European, African and Asian, integrated into local Xhosa and Khoi communities.[112] Right through to the British occupation of the Cape, the Slave and Free Black population together outnumbered European settlers.

over 150 000 can first be recorded between 1600 – 1652 during which 1071 ships on outward bound journeys alone stopped off at Table Bay and stayed for durations of 3 weeks to nine months.[110] This first formal attempt at colonisation occurred in 1615 when the English East India Company settled ten Newgate Convicts at Table Bay but this was a failure[111]. In 1652 the United Dutch East India Company established a refreshment station at Table Bay and in 1657 this was expanded to create the beginning of the Cape Colony. From the earliest of maritime journeys along the wild eastern coast of South Africa ships were wrecked and marooned survivors – European, African and Asian, integrated into local Xhosa and Khoi communities.[112] Right through to the British occupation of the Cape, the Slave and Free Black population together outnumbered European settlers.

In 1798 the first population figures given by the British Administration put the Europeans at 20 000, the slaves at 25 754, the Free Blacks at 1 700 and Colony Khoi at 14 447 but then by 1820 with new English settlers and troops pouring into the colony there was 42 975 Europeans, 31 779 Slaves, 1932 Free Blacks and 26975 Colony Khoi.[113]

Records show many inter-ethnic marriages and many children born of inter-ethnic relationships, liaisons or on the negative side as a result of molestation of masters of slave and Khoi women. Academic genealogical studies show that overall there is 6.9% black ancestry in the white Afro-European population (white Afrikaners, English and other European descendants of various waves of settlers) but in some white families there is up to 20% black ancestry in families.[114] The same applies among people classified as ‘Coloured’ where there is a similar wide variation within similar measurement parameters relating to ancestors of colour having procreated with Europeans. To a much lesser degree the same exists among people classified as ‘Black’ and ‘Indian/Asian’ in the Apartheid-silo paradigm. Genetic studies confirm social history and genealogical records.[115]

From the earliest of times in the Colony right through to modern times there were non-conformist Europeans who made common cause with people of colour and who assimilated into African-Creole or Camissa communities that were officially classified as ‘Coloured’. Likewise there were people of colour who assimilated totally into European society too. Within a few generations these fusions completed full circle.

While much is written about genealogy and dna of this aspect of genetic admixture and family ties ranging from 6.9% – 20% among some classified ‘White’ and some classified ‘Coloured’, the more interesting element exists in the social history of the conscious-rebel or non-Conformist Europeans who chose to sink their identity with people who were 80% – 93% African-Asian, (predominantly 70% African) in dna, genealogy and social history.

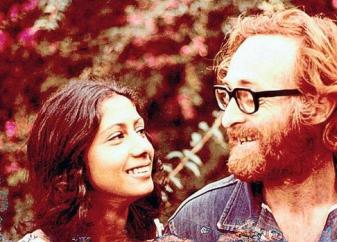

What is meant by ‘Non-Conformist Europeans’? They appear throughout the four-hundred years of history since the early 1600s to the present as people who walked against the tide of racism and colonialism. These are people who not only married and had children with people of colour, but sided with them against the Europeans and championed their cause as though it were their own, regardless of what was thrown at them while merging their entire lives, for better or worse with Indigenous Africans and the African-Creole or Camissa population. Often they physically left European society and subjected  themselves to hardships, norms, values and direction of community leaders. Some were executed for their deeds from slave revolt leader James Hooper in 1808 to ARM freedom fighter John Harris in 1964, while others lost their lives in the course of the war against Apartheid like Jeanette Curtis Schoon, Rick Turner and Ruth First, or were killed in detention like Neil Aggett. They remained true to their African communities until death. Descendants born of non-conformist progenitors were part of future generations of African-Creole communities. Good examples of such historical figures who have left African-Creole descendants are Coenrad de Buys and Dr Johannes van der Kemp in older history and, Dr Rick Turner, Barry Gilder, Elna Boesak, Johnny Carneson and many others in modern history.

themselves to hardships, norms, values and direction of community leaders. Some were executed for their deeds from slave revolt leader James Hooper in 1808 to ARM freedom fighter John Harris in 1964, while others lost their lives in the course of the war against Apartheid like Jeanette Curtis Schoon, Rick Turner and Ruth First, or were killed in detention like Neil Aggett. They remained true to their African communities until death. Descendants born of non-conformist progenitors were part of future generations of African-Creole communities. Good examples of such historical figures who have left African-Creole descendants are Coenrad de Buys and Dr Johannes van der Kemp in older history and, Dr Rick Turner, Barry Gilder, Elna Boesak, Johnny Carneson and many others in modern history.

Other European Non-Conformists who did not marry or have children with people of colour but through their life’s dedication and service in struggle for justice and against race supremacy and colonialism certainly also left a legacy contribution to the collective culture African-Creole or Camissa people. People like Bram and Molly Fischer, Springbok Legionnaires and Umkhonto we Sizwe leaders Wolfie Kodesh and Joe Slovo. There were also those like battle of Britain Spitfire ace pilot Wing Commander Adolf ‘Sailor’ Malan who led anti-Apartheid Torch Commando protestors.[116] There is a long and illustrious list of these champions, many of whom had children and grandchildren who married people of colour and also in this manner they take their place in the broad canvas of ancestral and cultural contribution to the whole. They give definition to the Afro-European cultural heritage rather than to the race-framed identity of ‘whiteness’.

Other European Non-Conformists who did not marry or have children with people of colour but through their life’s dedication and service in struggle for justice and against race supremacy and colonialism certainly also left a legacy contribution to the collective culture African-Creole or Camissa people. People like Bram and Molly Fischer, Springbok Legionnaires and Umkhonto we Sizwe leaders Wolfie Kodesh and Joe Slovo. There were also those like battle of Britain Spitfire ace pilot Wing Commander Adolf ‘Sailor’ Malan who led anti-Apartheid Torch Commando protestors.[116] There is a long and illustrious list of these champions, many of whom had children and grandchildren who married people of colour and also in this manner they take their place in the broad canvas of ancestral and cultural contribution to the whole. They give definition to the Afro-European cultural heritage rather than to the race-framed identity of ‘whiteness’.

Camissa Africans who are conscious of their African-Creole heritage express that they have everything to be proud of and to celebrate in acknowledging that such Afro-Europeans participated in struggles and are part of the Peopling of the Cape and the foundations of the African-Creole or Camissa legacy.[117]

It is really important that the perspective of the Non-Conformist European who is not preoccupied with ‘whiteness’ as an identity and fully embraces Africa and he people as Afro-Europeans is understood as an important part, but nonetheless just one part of a much bigger story. The notion that people are labelled ‘Coloured’ – simply argued as a mix of black and white is a fatally flawed and factually incorrect definition. The small element of admixture must be seen in the bigger context of all the tributaries to Camissa ancestry, culture and social history. The social history of rebel Afro-Europeans has too often been covered up and even negated. It is an important part of a bigger struggle of an African-Creole people who definitively emerge as a people who rose up against adversity – the adversity of Colonialism, successive Forced Removals and dispossession of land and livelihoods, Ethnocide, Genocide, de-Africanisation and Apartheid – all CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY.

7. CAMISSA – LOSS OF LAND, LIVESTOCK, RESOURCES,SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS, CULTURAL COHESION, LOSS OF LIBERTY AND IDENTITIES

Any appraisal of the Camissa African-Creole people should take into consideration the adversity experience and their rising above such adversity as it is this more than anything else that defines them. As descendants of over 150 tributaries, each with a story of adversity and struggles to overcome such adversity, they are survivors of what today would be recognised as Crimes Against Humanity[118]. This community has a strong case to make for restorative justice and reinstitution. The majority of their descendants, despite the existence of a small middle class, still live in poverty and with many social problems that link back to generationally transmitted trauma. Despite having a small middle class that share the standards of other African middle-classes and that of the white minority, the majority of Camissa Africans life experience and conditions are no different to that of other Africans in South Africa.

else that defines them. As descendants of over 150 tributaries, each with a story of adversity and struggles to overcome such adversity, they are survivors of what today would be recognised as Crimes Against Humanity[118]. This community has a strong case to make for restorative justice and reinstitution. The majority of their descendants, despite the existence of a small middle class, still live in poverty and with many social problems that link back to generationally transmitted trauma. Despite having a small middle class that share the standards of other African middle-classes and that of the white minority, the majority of Camissa Africans life experience and conditions are no different to that of other Africans in South Africa.

The San and the Khoi people systematically had their land, water resources and  livestock expropriated from them without compensation and were subjected to war and conquest when they resisted. The United Dutch East India Company (VOC) in addition to the use of force used three legal instruments[119] to expropriate the land of the indigenous people – Land Grants, Grazing Licences and Leasehold Farm Bonds (Leningplaats). When the British took over the Cape Colony they introduced Freehold Bonds. The modus operandi was to issue Grazing Licences for trek-boers to move onto the lands of the Indigenous people. This was followed by conflict over grazing land and water and the conflict would be concluded by war and appropriation of the land using the Leningplaats system, whereby the land was bonded to the VOC and loaned to the European farmer who had to pay the VOC with 10% of his annual profit. To accomplish the colonisation of the territory the Europeans murdered their way across the territory they seized. The loss of life was huge where 16 wars can be identified from 1652 – 1828. These wars dovetailed with and were continued in the form of the Eastern Cape wars where this continuum of war only concluded after another 50 years of wars in the Cape Colony up to the 1880s[120].

livestock expropriated from them without compensation and were subjected to war and conquest when they resisted. The United Dutch East India Company (VOC) in addition to the use of force used three legal instruments[119] to expropriate the land of the indigenous people – Land Grants, Grazing Licences and Leasehold Farm Bonds (Leningplaats). When the British took over the Cape Colony they introduced Freehold Bonds. The modus operandi was to issue Grazing Licences for trek-boers to move onto the lands of the Indigenous people. This was followed by conflict over grazing land and water and the conflict would be concluded by war and appropriation of the land using the Leningplaats system, whereby the land was bonded to the VOC and loaned to the European farmer who had to pay the VOC with 10% of his annual profit. To accomplish the colonisation of the territory the Europeans murdered their way across the territory they seized. The loss of life was huge where 16 wars can be identified from 1652 – 1828. These wars dovetailed with and were continued in the form of the Eastern Cape wars where this continuum of war only concluded after another 50 years of wars in the Cape Colony up to the 1880s[120].

- Autshumao’s cold war for Dutch containment 1652 – 1658

- 1st Dutch-Khoi war for the Peninsular 1659-1660

- 2nd Dutch-Khoi war – the war on Oedesoa and Gonnema 1673 – 1677

- 3rd Dutch-Khoi war – Ubiqua/Sonqua war 1701 – 1705

- 4th Dutch-Khoi war – The Namaqua and Ubiqua Stellenbosch District frontier war 1712 -1716

- 5th Dutch-Khoi war on two fronts – Gonaqua (East front & Namaqua west front) 1719 – 1737

- 6th Dutch-Khoi war – War of the consolidation of three district frontiers 1738 – 1739

- 7th Dutch-Khoi war – Rebellions of the Roggeveld and Hantam districts 1770 – 1772

- The 1st General Commando war – The ǀXamka war against the Cape san (ǀXam and !Xun) 1774

- The 2nd General Commando war – The Genocide offensive in the drive against Koerikei 1775 – 1777

- The 3rd General commando war – The 10 year offensive against the ǀXam Resistance in ǀXamka 1778 – 1789

- The United Khoi-Gqunukwebe Confederacy war – 1st Zuurveld war 1779 – 1781 (aka 1st Xhosa war of resistance)

- The United Khoi-Gqunukhwebe Confederacy war – 2nd Zuurveld war 1789 – 1793 (aka 2nd Xhosa war of resistance)

- The United Khoi-Gqunukhwebe Confederacy war – 3rd Zuurveld war 1799 – 1803 (aka 3rd Xhosa war of resistance)

- The British scorched-earth offensive against Khoi-Gqunukhwebe – 4th Zuurveld war 1811 – 1812 (aka 4th Xhosa war of resistance)

- The British war against the Xhosa and Khoi allies – Makhanda & Stuurman’s War 1818 – 1819 (aka 5th Xhosa war of resistance) This was followed by the first large-scale British settler invasion of Xhosa and Khoi lands when from 1820 over 5000 settlers were shipped to South Africa. (aka 5th Xhosa war of resistance)

Makhanda and David Stuurman were part of a rebellion on Robben Island in 1820 by 30 prisoners during which they escaped. Makhanda drowned at Bloubergstrand during the escape but Khoi leader David Stuurman escaped. He was the only person to have successfully escaped on two occasions from Robben Island and on his third capture he was exiled to Sydney in Australia where he died[121].

Makhanda and David Stuurman were part of a rebellion on Robben Island in 1820 by 30 prisoners during which they escaped. Makhanda drowned at Bloubergstrand during the escape but Khoi leader David Stuurman escaped. He was the only person to have successfully escaped on two occasions from Robben Island and on his third capture he was exiled to Sydney in Australia where he died[121].

In 1808 there was also the largest Slave Rebellion – The Jij Rebellion[122] – which also involved Khoi rebels and two non-conformist Europeans. It was followed by the largest ever Treason Trial after which five of the leaders were executed including the overall leader Louis van Mauritius and the Irishman James Hooper. This was followed by a smaller slave rebellion in 1825, and by the proclamation of Ordinance 50 of 1828[123] this phase of repression and resistance ended.

involved Khoi rebels and two non-conformist Europeans. It was followed by the largest ever Treason Trial after which five of the leaders were executed including the overall leader Louis van Mauritius and the Irishman James Hooper. This was followed by a smaller slave rebellion in 1825, and by the proclamation of Ordinance 50 of 1828[123] this phase of repression and resistance ended.

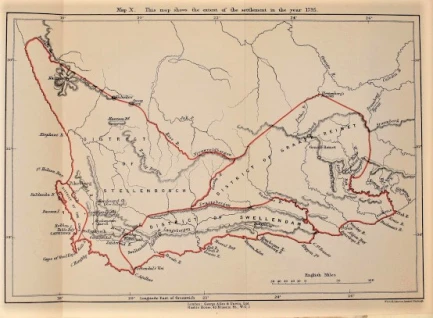

The livestock of the indigenes and the water resources were grabbed by the Europeans and the indigene farmer was impoverished, pacified and turned into farm-workers or conscripts into commandos which then carried out atrocities on any other Khoi or San community who stood in the way. The San people who put up greatest resistance were simply exterminated in recorded acts of genocide. The Khoi people faced only two options – pacification and destruction of their institutions of social cohesion, or to flee and seek refuge ever northwards. Through this conquest of land first the Cape District, then the Stellenbosch District, Swellendam District, Graaff Reinet District and finally the Zuurveld were created step by step and this became the Cape Colony which later further expanded to its borders when the Union of South Africa was established.

To control the indigenous people and slaves, the slaves were the first to have pass laws imposed on them by the Europeans to curtail their freedom of movement using the ‘licentiebrief’ over 180 years[124]. After the first forced removal and expulsion of Khoi from the Cape Peninsula in 1660, measures were put in place to control their movements from 1707 and full-blown pass laws enacted in the Caledon Proclamation of 1808[125].

Slaves like the indigenous people were subject to expropriation without compensation. The Europeans would never have been able to manage livestock herds, nor to turn wild virgin territory into agriculturally productive land without slave labour. Slave labour also developed roads, towns and homes for the Europeans. Slaves worked under cruel torturous conditions and were unpaid forced labour. It was slaves that added productive increasing value to farmlands off which the Europeans profited and prospered. When slavery ended in 1834, slaves had to pay compensation to the Europeans in the form of a four year apprenticeship before they could be freed. The British government also compensated the slave owners financially for each of their freed slaves.[126] Slaves and their descendants were never given restorative justice and compensated for this crime against humanity.

Khoi and Slaves were subjected to pacification processes that included the ‘Tot-System’ where daily rations of alcohol were fed to them as a form of ‘compensation’. This has resulted in substance abuse problems to this day and to alcoholic foetal syndrome where children are born alcoholics. The daily diet of violence by European slave owners on slaves and also on Khoi apprentices together with the constant-warring legacy has contributed to the high rates of homicide and violence in society to this day[127]. Acts of violation, torture, rape, murder and enforced concubineage in the genocide[128] sprees against the Cape San (ǀXam and !Xun) has left deep scars. San children were abducted to farms after their parents executed. The taking of farm-children from their parents to cities to work as servants in homes continued right throughout the 20th century too. During the Apartheid years children who were of lighter complexion were taken from families and put into Children’s Homes as a means to transition them into assimilation into white society. The array of indignities and adversities carried out by colonialism and Apartheid on Camissa Africans and their forebears is a tale of sheer horror.